Thailand’s integration of national data systems revealed over a million children who had previously been overlooked by the educational system, shining a light on the vast scale of educational exclusion. This discovery has brought to the forefront the urgent challenges of reintegrating these children and ensuring they stay in school. In the first of this three-part article series, Dr. Kraiyos Patrawart, the Managing Director of the Equitable Education Fund (EEF) Thailand, explains how the identification of out-of-school children became possible, setting the groundwork for the next step: creating effective strategies to bring these children back into the educational system and prevent future dropouts.

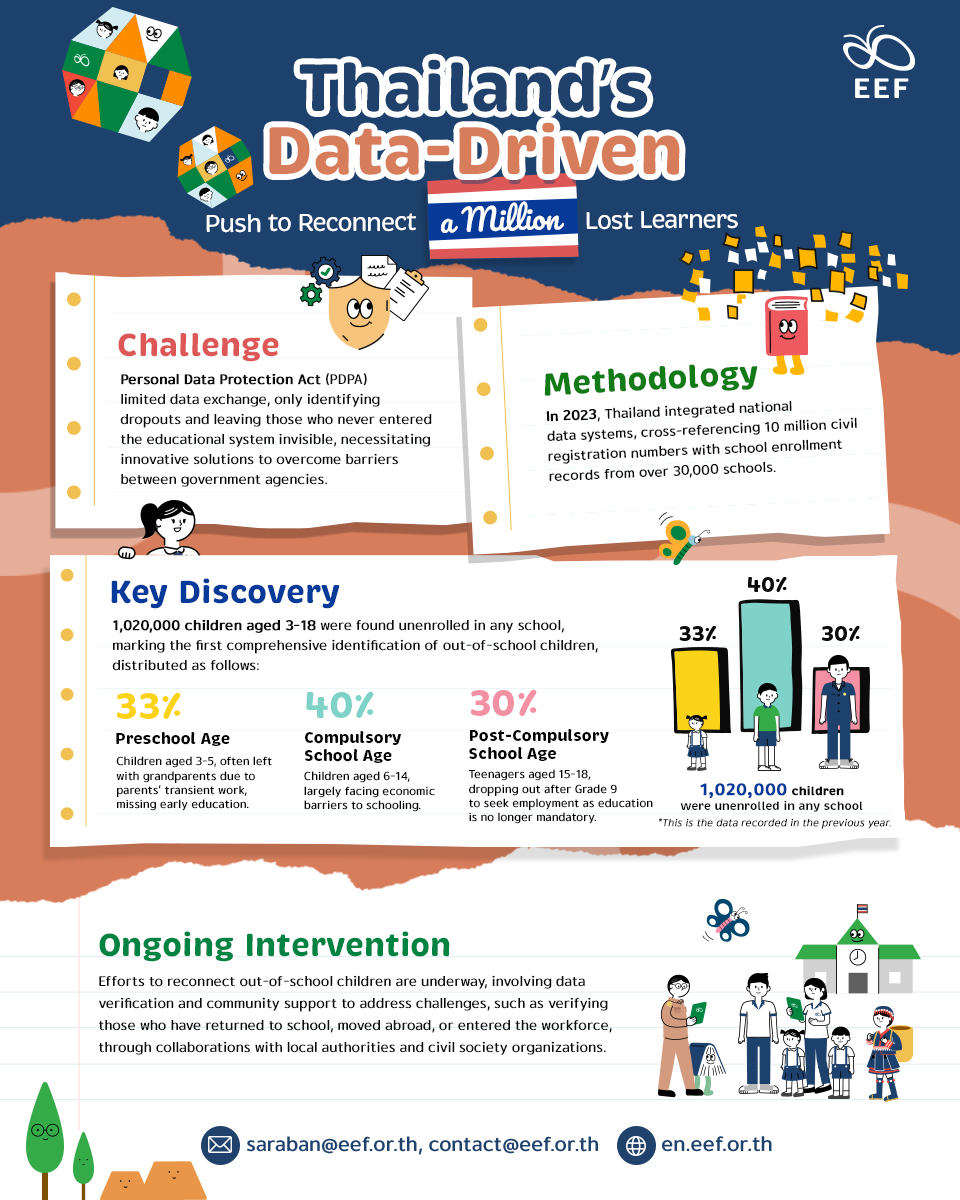

Thailand’s Data-Driven Push to Reconnect a Million Lost Learners

Challenge

Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) limited data exchange,

only identifying dropouts and leaving those who never entered the educational system invisible, necessitating innovative solutions to overcome barriers between government agencies.

Methodology

In 2023, Thailand integrated national data systems,

cross-referencing 10 million civil registration numbers

with school enrollment records from over 30,000 schools.

Key Discovery

1,020,000 children aged 3-18 were found unenrolled in any school,

marking the first comprehensive identification of out-of-school children,

distributed as follows:

- 33% Preschool Age: Children aged 3-5, often left with grandparents due to parents’ transient work, missing early education.

- 40% Compulsory School Age: Children aged 6-14, largely facing economic barriers to schooling.

- 30% Post-Compulsory School Age: Teenagers aged 15-18, dropping out after Grade 9 to seek employment as education is no longer mandatory.

Ongoing Intervention

Efforts to reconnect out-of-school children are underway,

involving data verification and community support to address challenges,

such as verifying those who have returned to school, moved abroad, or entered the workforce,

through collaborations with local authorities and civil society organizations.

In 2023, Thailand took a groundbreaking step to confront educational exclusion by integrating national data systems for the first time. This unprecedented move revealed a stark reality: a significant number of children were entirely absent from the formal school system. What had once been hidden behind estimates became an undeniable truth, one that could no longer be ignored. At the heart of national decision-making, evidence now guides educational reforms, reshaping the country’s approach to reaching its most vulnerable learners and ensuring no child is left behind.

Dr. Kraiyos Patrawart, the Managing Director of the EEF, shared the impact of this initiative: “For the first time in 2023, we successfully connected data nationwide using Thailand’s civil registration numbers—13-digit IDs that every Thai citizen holds for life. We cross-tabulated the records of over 10 million children aged 3 to 18 with school registration data from more than 30,000 schools across the country—public, municipal, and private. What we discovered was striking: over 1,020,000 children had no record in any school system. That’s how we identified our out-of-school population for the first time. We repeated the exercise in 2024, and while the numbers dropped slightly thanks to government efforts like the Zero Dropout initiative, this was our foundational step in using data to drive real educational change.”

The breakthrough also came with overcoming the constraints of the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA), a challenge that required creative problem-solving. Before, the system could only identify students who had dropped out, leaving those who had never entered the educational system completely invisible.

Dr. Kraiyos Patrawart explained, “Ignoring the weight of this gap was no longer an option. In the past, schools could only identify dropouts by comparing students who enrolled one year but didn’t return the next. This meant we missed children who never entered the system—those who delayed entry or those with disabilities who had no schools to accommodate them. Thanks to connected computer systems, barriers that once kept critical information siloed were dismantled. We can now capture the full picture of out-of-school children—not just those who left, but those who were never included in the first place; every child is now seen, counted, and supported”

Reconnecting with one million students outside the educational system brought forth yet another set of challenges. Tracking their whereabouts revealed not only logistical difficulties but also profound socio-economic barriers that hinder children’s access to formal education. These children face challenges ranging from early work commitments to relocations abroad and delayed school entry.

In the process, the Managing Director emphasized that understanding the distribution of these students is essential for developing tailored strategies and requires immediate, coordinated action to address systemic inequalities in education, stating “We gathered names, addresses, and details, relying on on-the-ground volunteers and civil society agencies to reach out. We found that many students had already returned to school, while others had gone abroad for studies, particularly those from Muslim families. The majority, however, fell into three distinct groups: preschoolers, often from low-income families, who wait until they turn six to start school; children aged 15 to 18, who drop out after compulsory schooling to find work but hope to return to education later; and the post-compulsory school age group, which made up 30%, 40%, and 30% of the total, respectively.”

Notably, the lack of early education, especially among children in low-income families, is a critical issue in Thailand. Dr. Kraiyos Patrawart highlighted the need for intervention: “Identifying out-of-school preschoolers makes a real difference. In urban areas, children of workers at construction sites often play in makeshift learning spaces set up by developers. Meanwhile, in rural areas, young children are left with grandparents while their parents work in the city, only starting school at ages 5 or 6. This is common in low-income families but raises concerns about developmental delays compared to their preschool peers.”

For Dr. Kraiyos Patrawart, this issue is not just about child development; it’s an economic concern too, given Thailand’s aging population and shrinking workforce. “We’re launching a research project to understand why 300,000 children miss out on early education, all based on evidence,” he added, offering a glimpse into what lies ahead with the EEF-spearheaded Thailand Zero Dropout initiative.

Nonetheless, identifying these gaps is just the beginning; the true challenge lies in reintegrating these children into the educational system and developing strategies to maintain their engagement. In the first article of this three-part series, we examined Thailand’s groundbreaking use of national data systems, which uncovered over a million previously unseen children and highlighted the barriers they face, particularly in accessing early education and overcoming socio-economic challenges. With these insights, Thailand is now poised to address these disparities through targeted interventions, a mission embodied by the Equitable Education Fund (EEF) Thailand, which aims to reduce educational inequality through research, collaboration, and support for those most in need. The next installment will focus on the strategies needed to reintegrate these children, break the cycle of exclusion, and prevent future dropouts, ensuring their long-term success.

All For Education is all about people; only when all is in for education is Education For All. Join the movement to reduce educational inequality. Support the EEF by donating to fund research, partnerships, and assistance for children, youth, and adults in need of educational support. Click the link to contribute today and help create a society where education is open and equal for all. Together, we can make a lasting impact.