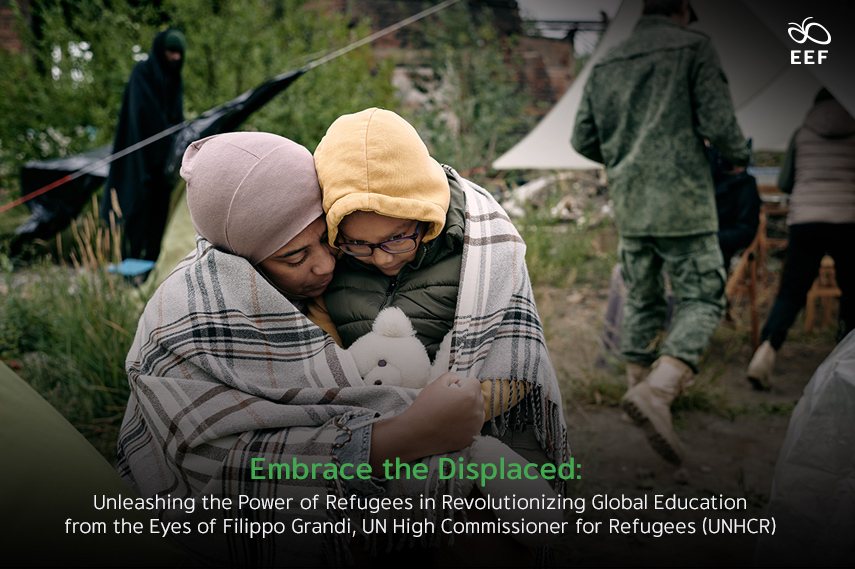

In a world plagued by pernicious humanitarian emergencies and prolonged displacement, the fate of refugee children and adolescents hangs in the precarious balance. Regardless of their location, when forced to flee their homes, their lives are thrown into turmoil. These young individuals had once been eagerly attending school or university, building knowledge, acquiring skills, forging friendships, and envisioning their futures. However, all it took was one moment when their lives were in danger, for all that to be cruelly snatched away.

Once access to education has been lost, reclaiming it becomes a daunting challenge. Trapped in protracted crises, countless young refugees find themselves deprived of education. Even before the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly half of these aspiring minds were unjustly squeezed out of school. Year after year for the past decade, as forced displacement reaches staggering heights, millions of young refugees are cruelly pushed out of the realm of educational possibilities. Most of them — over four in five — find themselves in low and middle-income countries, with more than a quarter residing in the world’s most underdeveloped regions. And the harsh reality is that some of these young learners may not have a school to go to, while others may confront an unfathomable choice between educational expenses and their most fundamental survival needs. Juggling the costs of textbooks, transportation, and fees against the essential requirements of sustenance, shelter, and healthcare, the very notion of “opportunity” becomes elusive.

This crisis, if left unaddressed, undermines the achievement of UN Sustainable Development Goal 4 — the promise of inclusive and equitable quality education for all. Across his recent journeys, spanning from Ukraine to the Sahel, from Bangladesh and beyond, UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Filippo Grandi has witnessed the fervor and unwavering thirst for knowledge within refugee communities.

These young individuals deserve more than just sporadic lessons in makeshift schools. They deserve a comprehensive and high-quality education within formal education systems. The significance of including refugee children and adolescents in these systems, bolstering their strength and accessibility, cannot be emphasized enough. Poor-quality education and limited access to schools plague not only refugees but hundreds of millions of children worldwide. However, the plight of young refugees is particularly acute.

On this note, gaining insights from comprehensive data on refugee enrolment, UNHCR has unveiled a compelling narrative on the state of refugee education. The data from over 40 countries highlights a troubling reality: refugee children and adolescents are lagging behind their non-refugee counterparts in accessing inclusive quality education.

Enrolment rates fluctuate across different levels, showcasing both strides and setbacks. While the rates for pre-primary and primary education remain steady at 42 and 68% respectively, there is a significant drop to 37% for secondary education compared to the previous year. While the rates for tertiary education have improved to 6%, they still fall behind global standards, particularly in wealthier countries. Nevertheless, this marks significant progress compared to the previous years when only 1% of refugees were enrolled in tertiary education.

Refugee boys have a slight advantage over girls, with rates of 68% to 67% at the primary level, and 36% to 34% at the secondary level. However, collecting complete and accurate data in these challenging environments presents numerous difficulties. According to the latest estimates from Education Cannot Wait, the UN’s global fund for education, approximately half of all school-age refugee children, accounting for 48%, are currently not attending school.

Access to education is significantly influenced by inequality. Primary education shows high enrolment rates close to 100% across all income brackets, far exceeding rates for refugees. However, the situation changes for secondary education, where enrolment rates decline following a country’s income level. Only in low-income countries do the rates come closer to those observed among refugees, ironically highlighting the striking disparity faced by young refugees in their pursuit of equal opportunities

Refugees, facing significant disadvantages, find themselves among the most marginalized individuals. To emphasize this point further, a comparison was conducted in nine countries, examining the proportion of out-of-school refugee children and adolescents to their host-country equivalents from both the lowest and highest income brackets. This vividly illustrates the limited educational opportunities available to refugee children and adolescents, as well as to their poorest host-country counterparts — refugee children and adolescents fare as badly as their non-refugee peers in the poorest sections of society.

However, in certain instances, refugees fare even worse. For instance, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which housed approximately 490,000 refugees in 2020, the out-of-school rate stands at 65% for refugees, while it is only 35% for children from the lowest income quintile, the poorest 20% of the population, and a mere 6% for the wealthiest quintile, showcasing the immense disparities among these three groups.

Amidst an ongoing learning crisis, there are glimpses of success that offer hope. For the first time in UNHCR’s education report, data on national academic assessments are presented, aiming to gain insights into the educational progress of refugee students. This is crucial, considering the prevailing learning crisis in many countries where a staggering 57% of children in low and middle-income countries struggle to read and comprehend a simple story by the end of primary school, with figures soaring to over 80% in low-income countries.

Unfortunately, the most vulnerable individuals bear the brunt of learning inequality, which has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic-induced school closures. As 83% of refugees and displaced Venezuelans find refuge in low and middle-income countries, the ramifications of this inequality are concerning. However, when examining exam results, refugee students exhibit a remarkable record of achievement. In 23 reporting countries, 74% of primary-level refugee students successfully passed national tests, while the corresponding figures for lower and upper secondary levels were 65 and 63% respectively.

It is important to note that the number of refugees participating in these national tests is often small. For instance, in Cameroon, a pass rate of 74% at the lower secondary level is based on a mere 154 refugee students taking the exams. Nevertheless, it reinforces the notion that when given the opportunity, refugee students seize it wholeheartedly. However, there also exists a significant gender imbalance when it comes to exam participation. Among refugee students who took national tests in our reporting countries, only 39% were girls at the primary level. The figures for girls sitting lower and upper secondary level exams were 44 and 43% respectively.

Additionally, classrooms that accommodate refugee children and adolescents are often overcrowded, hindering effective teaching and learning experiences — a contrast between demand and supply. Data on teachers are scarce and difficult to obtain, but a few countries have reported teacher-to-pupil ratios in refugee communities, revealing the prevalence of excessively crowded classrooms that surpass recommended ratios.

In eight countries across Sub-Saharan Africa, the pupil-to-teacher ratios were considerably higher for refugee children and adolescents compared to nationals. For example, in Burkina Faso, there were 40 national learners per teacher, while for refugees, the ratio increased to 60:1. Similarly, in Zimbabwe, the ratio for nationals was 36:1, while for refugees, it spiked to 59:1. In all instances, the overcrowded classes posed challenges for effective teaching, highlighting both the demand for education and the strain on available resources.

To reverse the current tide, a monumental and united effort is imperative. It is crucial to ensure that refugee children and adolescents receive education from competent and well-prepared teachers. They deserve access to formal education systems that employ up-to-date curricula and accredited materials of excellent quality. To achieve this, robust policies that guarantee the inclusion of young refugees in the national education systems of host countries must be established. Simultaneously, these countries require adequate financial resources to incorporate displaced children into their educational frameworks. To reverse the current tide, it is crucial to ensure that refugee children and adolescents receive education from competent and well-prepared teachers and gain access to formal education systems that employ up-to-date curricula and accredited materials of excellent quality. Moreover, host countries establish robust policies that guarantee the inclusion of young refugees in their national education systems and allocate adequate financial resources to incorporate displaced children into their educational frameworks.

Education is not merely an expenditure, but rather an investment in the realms of development, human rights, and peace. Now is not the time to diminish overseas development aid, thereby depleting resources for education; instead, it is the time to channel our resources toward nurturing the futures of aspiring builders, creators, and peacemakers. For refugees, this investment becomes the bedrock upon which they will rebuild their countries of origin when the time comes for their safe return.

On the ground, UNHCR and its invaluable partners necessitate continuous and heightened support to persevere in their crucial work. This entails ensuring that teachers receive fair compensation, constructing and expanding school infrastructure, fostering community engagement to illuminate the value and rewards of education for children and adolescents, facilitating safe access to schools, providing transportation, and accomplishing numerous other tasks. The past years have yielded significant progress. The 2018 Global Compact on Refugees has garnered immense support for UNHCR and its partners, particularly in the realm of education, catalyzing vital policy changes that enhance the inclusion of refugees in formal education systems. Now, we must align these transformative changes with substantial and sustained funding, solidifying our advantage in inclusive policies.

This year, UNHCR’s annual education report coincides with the Transforming Education Summit, convened by the UN Secretary-General during the 77th session of the General Assembly. The Summit aspires to mobilize action, ambition, solidarity, and solutions, seeking to revolutionize education by 2030. Refugee children and adolescents must be integral to this transformation. Investing in their education is a collective responsibility that reaps far-reaching collective rewards. It will contribute to a more peaceful, resilient, and just world. Moreover, it will bridge the daunting chasm that separates talent from opportunity. The repercussions of failing to undertake this crucial mission will be overwhelmingly immense.

Source: https://www.unhcr.org/media/unhcr-education-report-2022-all-inclusive-campaign-refugee-education