Pre-COVID-19, some estimated that there was an annual financing gap of US$148 billion in lower and middle-income countries to achieve the education systems envisioned by the 2030 Agenda, and that was so huge a gap between the resources that are currently made available and the resources that would be necessary to do so. Unless necessary action is taken, the period of fiscal constraint brought about by the prolongation of the pandemic might result in a growth in the financing gap for education in lower and middle-income countries to as much as US$200 billion annually. It is worth mentioning that climate change and subsequent ecosystem destabilization will present new challenges to ensuring the right to education, be it teacher and student displacement, damage to school infrastructures, food insecurity, disease, and poverty, particularly for the most vulnerable — all of which have significant financing implications.

Around the world, at all income levels, there are still; however, many countries that fall short of the commitments made at the 2015 World Education Forum in Incheon of allocating at least 4-6% of their GDP and/or at least 15-20% of their total public expenditure to education. Certain trends towards obnoxiously crass commercialism and profiteering in education pose a challenge to its status as a public good and could transform it into a market good. The governance challenge is to ensure that, as non-state involvement in education policy, provision, and monitoring grows, multi-stakeholder involvement is always oriented at and focused on strengthening the equity, quality, and relevance of education as a public societal endeavor and the common good.

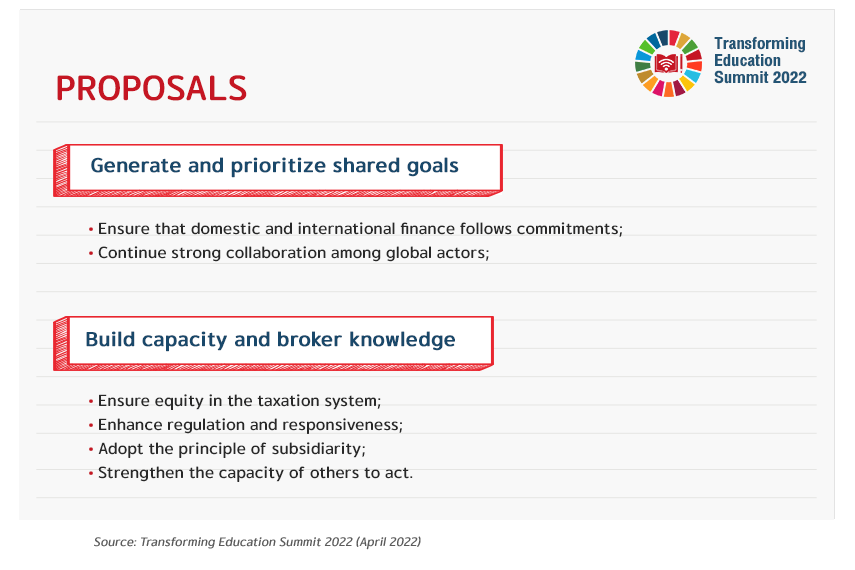

The good news is that the scales have tipped towards more equitable forms of international cooperation; An international architecture for educational cooperation, known as north-south, profoundly shaped by colonialism, which essentially is the domination of national economic and geopolitical interests, is being increasingly challenged as new forms of partnership — south-south, or even triangular forms of development cooperation, which are more equitable — are on the rise. Besides, there is increased civil society engagement and advocacy in education at local, national, and international scales; New partnerships among governments and non-state actors, be it teacher associations, youth movements, professional associations, or social movements, are making education increasingly present on the agendas of domestic, regional, and global political bodies. To secure adequate and sustainable financing, here are some proposals included in the Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education report of the International Commission on the Futures of Education.

Recognizing the need to decrease the cost burden of learners and raise the capacity of educational institutions, the Thai government has recently approved an increase of per capita subsidies based on necessities, starting in the fiscal year of 2023, or October 2022. A clear framework for the educational support and education budget will be considered to support educational resources that are efficient, equitable, fair, and consistent with changes, including monitoring the system’s fluidity and accountability. This is in line with the Paris Declaration: A Global Call for Investing in the Futures of Education, which calls on all governments to raise domestic resources with additional investments to recover from COVID-19. Innovative financing models, with the cooperation of stakeholders, most notably the Equitable Education Fund, Thailand, are now being introduced to ensure adequate funding for those underprivileged and vulnerable.

Source: Transforming Education Summit 2022 (April 2022)