The 2025 Thailand International Conference on Education Research (ThaiCER), organized by the Office of the Education Council (OEC), took place at the Asawin Grand Convention Hotel in Bangkok from August 7th-8th. Hosting partners include UNICEF Thailand, the Equitable Education Fund (EEF) Thailand, the Princess Maha Chakri Award Foundation, SEAMEO STEM-ED, and various agencies of the Ministry of Education (MOE). This year’s theme, “The Education for the Future Begins Today,” captures the urgency and promise of transforming education amid global shifts.

Global challenges like the Fourth Industrial Revolution, climate change, demographic transitions, and expanding social inequalities confront education systems worldwide. In response, education must steadfastly pursue quality and equity through evidence-based policies, digital innovation, and holistic human capital development. These efforts aim to build a knowledge-based society in Thailand—one that is resilient, competitive, and sustainable—fully aligned with the philosophy of sufficiency economy. Central to these ambitions is collaboration: the OEC has partnered with 15 organizations to advance this vision under this theme.

Among key contributors is Francois Staring, a policy analyst representing the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The OECD promotes economic and social development, with education as a vital pillar, and has played a crucial role in elevating Thai education standards through various cooperative projects and policy advisories. One prominent example is the partnership with the EEF on targeted research initiatives like “PISA for Schools,” which aims to explore ways to uplift disadvantaged students in remote areas.

At ThaiCER 2025, the featured lecture series titled “Evidence-Based Policy Formulation: Utilization of Educational Research Outputs” will focus on four pivotal topics. First, it introduces the OECD and articulates why educational research demands our attention. Following this, it explores how governments can support the development of knowledge infrastructure that underpins education. Third, it reviews the evolving roles of educators in this transformative landscape. Finally, it presents a set of guiding questions designed to stimulate dialogue and innovation during the Conference.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) was established in 1961 as part of the Marshall Plan, aiming to restore and rebuild Europe’s economic and social structures. Today, it comprises 38 member countries worldwide, with Colombia and Costa Rica joining most recently in 2020 and 2021. Starting in 2024, Indonesia and Thailand will become the first Southeast Asian countries to join as OECD candidate countries.

Thailand’s collaboration with OECD has spanned decades. Since 2001, Thailand has participated in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which evaluates student performance in reading, mathematics, and science. The country also joined OECD’s recent survey on creativity and critical thinking in schools. In recent years, OECD’s support has deepened, notably through the publication of strategic reports on skills development. As OECD’s representative, Francois views this conference as a vital opportunity to learn about Thailand’s educational system, understand its challenges and needs, and help chart pathways for future improvement.

Beyond Thailand, OECD works closely with governments worldwide to design, evaluate, and support the implementation of national educational policies. It operates the Center for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) dedicated to advancing education, focusing on identifying what truly matters in teaching and learning. OECD’s approach integrates three essential components—policy, practice, and research—to sustainably enhance student learning outcomes.

Why does educational research matter?

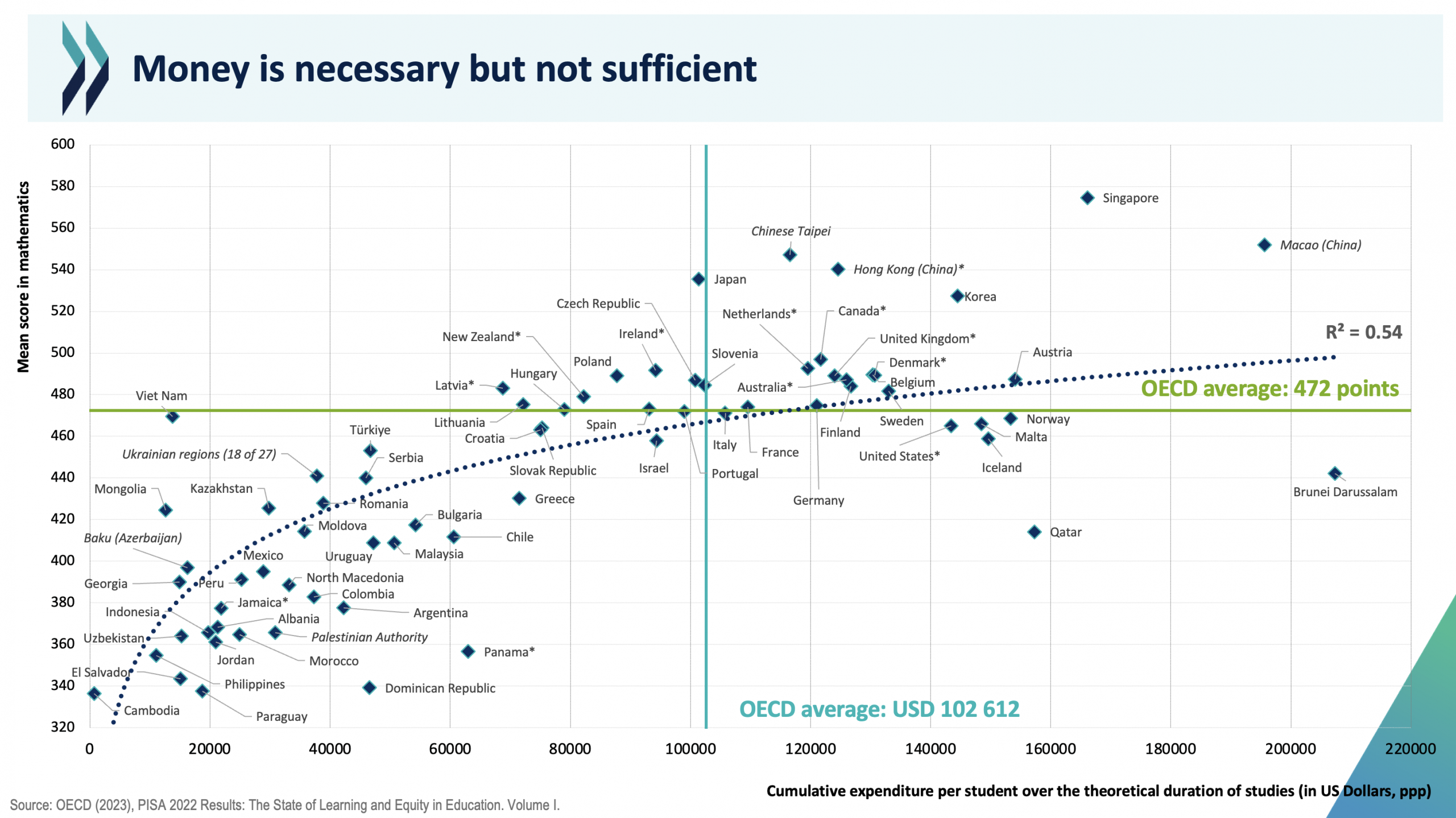

Francois highlights why OECD is deeply committed to advancing educational research. While funding undeniably plays a role, budget alone is insufficient to sustainably improve educational quality. To illustrate this, he presents compelling evidence.

The data shows Singapore invests less in education than Brunei, yet its students achieve significantly higher academic results. Similarly, Vietnam’s investment levels are comparable to Chile’s, but its learning outcomes surpass Chile’s by a wide margin. This clearly indicates that while funding matters, it is not the sole driver of learning success.

A second reason why OECD values educational research is to challenge the assumption that more time spent learning necessarily translates into better student outcomes. A graph of 15-year-old PISA test takers reveals the hours students spend learning weekly—in-school hours shown in blue, out-of-school learning in green. Countries like Finland and Switzerland have students who spend fewer hours learning yet outperform peers in Italy, Chile, and Thailand. This suggests that learning quality and instructional methods matter more than quantity of time.

Countries like Finland and Switzerland have students who spend fewer hours learning yet outperform peers in Italy, Chile, and Thailand. This suggests that learning quality and instructional methods matter more than quantity of time.

Francois Staring, a policy analyst representing the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

How does OECD help countries better connect policy with educational research practice?

At OECD’s CERI, a specialized team works specifically to bridge the gap between policy and research practice. Over the past five years, OECD has published three key reports—in 2021, 2023, and 2025—based on two main data sources. The first source is a survey conducted jointly with ministries of education, involving representatives from 29 of the 38 OECD member countries and 37 jurisdictions, to understand factors, barriers, and mechanisms for translating educational research into policy and practice. The second source, from a 2023 field survey, gathers input directly from 288 OECD research-producing and disseminating organizations across 34 countries.

How can governments develop the knowledge infrastructure for education?

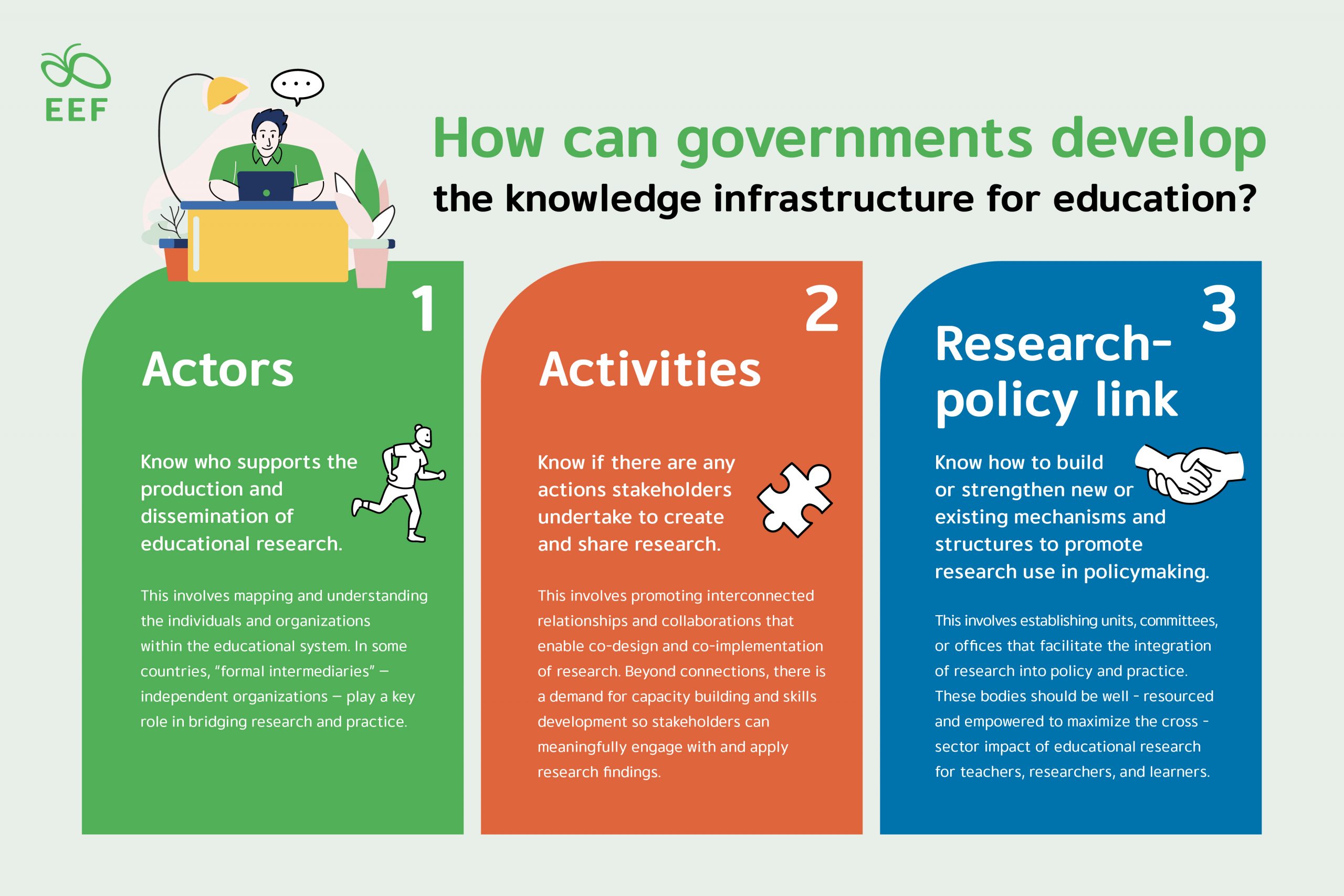

Francois emphasizes that the core of this presentation is to highlight the potential and opportunities governments have to build an enabling ecosystem that supports the use of research in policy-making and practice. This infrastructure consists of three key components:

3.1. Actors: Who supports the production and dissemination of educational research within the system?

When OECD begins working with a new member country, the primary task is to map and understand the individuals and organizations involved in the educational system. This process is complex and time-consuming due to the many stakeholders: teachers councils, teachers associations, local municipalities, state boards, national ministries, and various agencies.

In some countries, specific units within ministries champion research use; in others, these may lie outside ministries or involve strong collaboration between ministries and research institutes or universities. While each country’s network is unique, shaped by its cultural, historical, political, and traditional context, a clear trend over the past 10–15 years is the emergence of “formal intermediaries”—independent organizations dedicated to supporting research use at both policy and practice levels.

3.2. Activities: What actions do stakeholders undertake to create and share research?

Twenty years ago, research dissemination followed a linear path: scholars conducted studies at universities, published in academic journals, and eventually presented findings. However, such typical processes often fail to produce research that policymakers, teachers, and school leaders can effectively use.

What is truly needed are interconnected relationships and collaborations that enable co-design and co-implementation of research. Beyond connections, there is a demand for capacity building and skills development to apply and engage with research meaningfully. This calls for training teachers, school leaders, and policymakers on how to use research effectively, combined with incentives, adequate structures, resources, and dedicated time for research engagement.

One major barrier is that much research is seen as irrelevant to specific national policies, and many academic publications are inaccessible to policymakers or practitioners. Making research accessible in the form of best practices is essential. Moreover, there is a lack of capacity building processes, such as initial teacher training that integrates research development—an area OECD finds insufficiently emphasized. Teachers must develop competencies to access and interpret research independently, cultivating an initiative-driven mindset to explore new approaches when current teaching falls short.

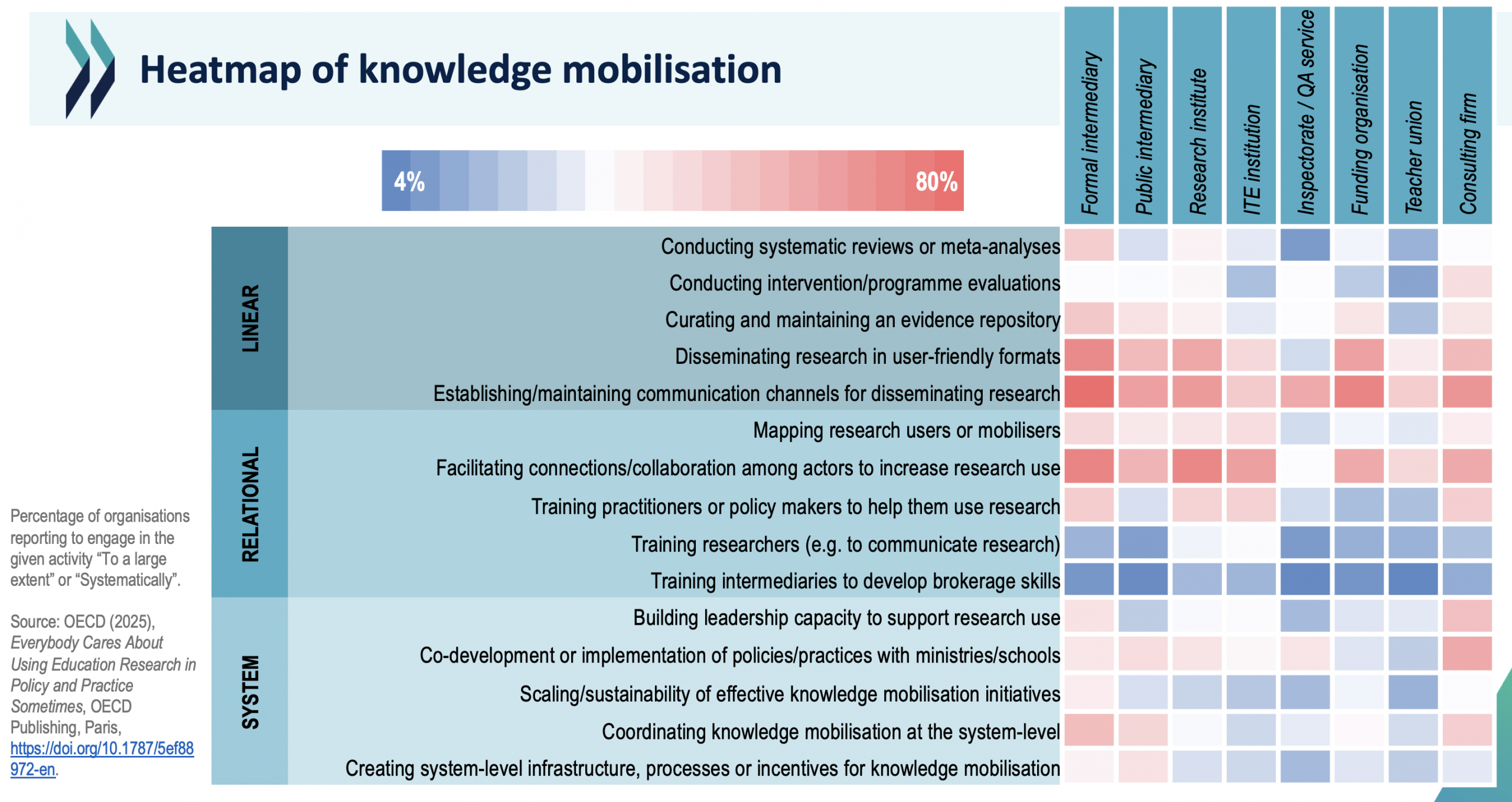

Once the producers and disseminators of research are identified, OECD creates a “heat map of knowledge mobilization”—an infrastructure analysis that categorizes organizations and activities involved in research use, as published in the 2000 report. This map includes formal intermediaries, government bodies, ministries, research institutes, teacher education institutions, consultancies, and more.

Organizations rate their engagement in various activities on a scale from 1 (low enthusiasm) to 5 (high enthusiasm). Cooler colors—such as blue—indicate less activity; warmer colors—like red—indicate more. Importantly, OECD does not expect all boxes to be “red” or highly active—overextending resources and causing unnecessary competition is counterproductive. Instead, only specialized roles or experts should be tasked with specific activities. For example, teacher education institutions might lead training on research engagement for future teachers.

Interestingly, only a few organizations typically coordinate the research dissemination ecosystem, including governments, formal intermediaries, and government-embedded agencies.

3.3. Research-Policy Link: How can new or existing mechanisms and structures be built or strengthened to promote research use in policymaking?

Francois gives examples: In Norway, the government collaborates with independent experts through “Public Committees” appointed by royal decree. These committees are resourced and empowered to work on research, evidence, and policy across sectors. In the Netherlands, a dedicated “Directorate for Knowledge” within the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science supports other departments to maximize the benefits of educational research.

Reviewing the Role of Educators:

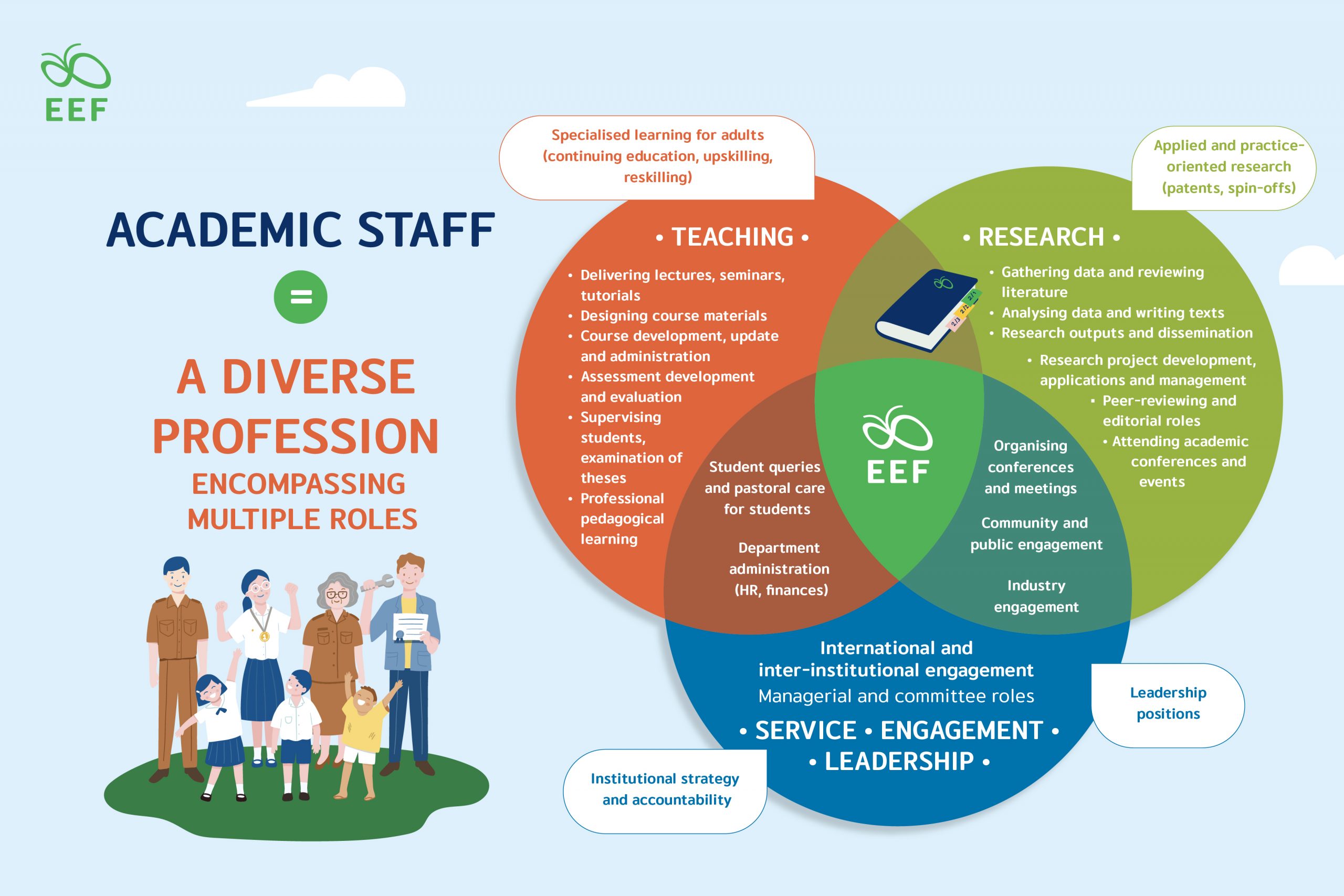

OECD, alongside ministries of education, organizations, research institutes, and formal intermediaries, studies who does what in educational research production and dissemination. Historically, educators were defined as multi-skilled professionals covering various roles. In the future, they will be recognized as multi-skilled experts with specific achievements.

Francois elaborates that university academics mainly juggle two roles: teaching and research. Their third role involves leadership, service, and collaboration with external organizations. This complexity demands considerable effort. Academics are often evaluated based on the quantity of publications, journal rankings, and research projects. While teaching quality may affect promotions, community engagement and stakeholder collaboration rarely factor significantly into evaluations.

This significant gap has long been recognized, and many organizations are gradually shifting academic culture. This shift is evident in questions around motivation—such as attending conferences, collaborating with community members, or partnering with fellow educators. Such motivations ideally stem from researchers’ personal desires or beliefs that these actions are inherently valuable and socially impactful. External incentives, however, have more limitations. Examples include salary increases tied to successful research dissemination or performance evaluation criteria. Only about one-third of institutions have formal policies offering such external motivators. These realities suggest that educators must play a greater role in developing the research competencies of future teachers.

Guiding Questions for ThaiCER 2025

Francois concluded his lecture by presenting a set of compelling questions to inspire further reflection among participants. The first question invites consideration of key actors and activities, particularly within Thailand’s context or other national systems: Who are the individuals and organizations responsible for disseminating educational research, and how do they operate? Are there gaps in this system that still require development? How might personnel or institutions address and fill these gaps?

The second question probes the existing links between research and policy: What mechanisms and structures are already in place? Are there specialized advisory bodies? Are there ministry officials currently engaged in this work? How can existing expertise and capacity be further strengthened and leveraged?

Finally, the third question asks: How can we ensure that everything discussed and shared during these two days of the conference will not be lost? How can we build upon these conversations? And how can we guarantee that all the recommendations presented here will be genuinely considered by the OEC and the Thai government?